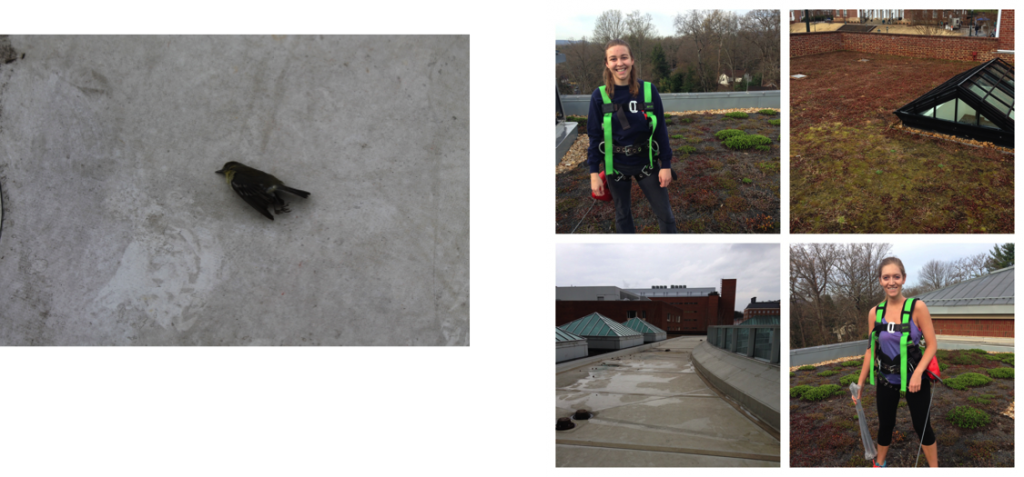

Everyday, hundreds of students walk across the courtyard on McCormick road in front of Alderman Library and the Library of Special Collections. Brick walkways crisscross between lush, green shapes of grass lawn and upraised sections with planted flowers and groomed shrubbery. Deceivingly, this courtyard is a functioning green-roof, on the top of the special collection library.

The upraised planters include a large rectangular window surrounded by short plants, herbs, and flowers. Plants in these must have short roots and have the ability to thrive in space-limited environments. Each planter has several sprinklers, and includes several species of plants within each cement oval.

Figure 1: A ceiling window from the interior of the library.

The design of the green roof not only offers green space for the public and exterior aesthetics of the building, but also creates an ideal space for studying. The study rooms underground are quiet, with little to no noise from traffic on McCormick road. The grass above actively cools and sound proofs the library below. Natural light from the ceiling windows illuminates the study rooms and reduces dependency for harsh, florescent lights for reading. From our visit last week, the atmosphere of the students was calm and focused, unlike the stress-intensive environment of the study areas in Clemons library just next door. Although the space is underground with limited visual of nature, it is still a considerable “biophilic” space, as the atmosphere is created by the nature growing around (and above) it.

Figure 2: Large shrubbery occupies the area near the entrance of the building.

One improvement to the space could be to label the species in the planters, or offer public participation for planting in the space. In front of the entrance, larger shrubbery and plants requiring mulch occupy the space, with benches for sitting along the edges and adjacent to the sidewalk. One could imagine plaques here that identify shrubs and plants around the benches and the herbs in sights view from the front of the building.

Although weight and plant-specific conditions must be considered, the large planters have the capacity for large plants and flowers, and is a potential area for high biodiversity; an ecological oasis in the middle of monotonous grass fields. A project for an environmental planning class, perhaps, could be to design the ideal courtyard planter that improves the space within the limitations of the roof.

Figure 3: The planters contain an upraised ceiling window as well as several small shrubs and short plants.

The cement planters provide a good environment for an herb garden and could be used for plants that are either aromatically or orally pleasing. Mint and rosemary, for example, could further contribute to a positive, academic environment, emitting soothing aromas. These areas receive plenty of sunlight for herbs, which would require limited maintenance and grow easily in open areas.

Post by Liz Helm