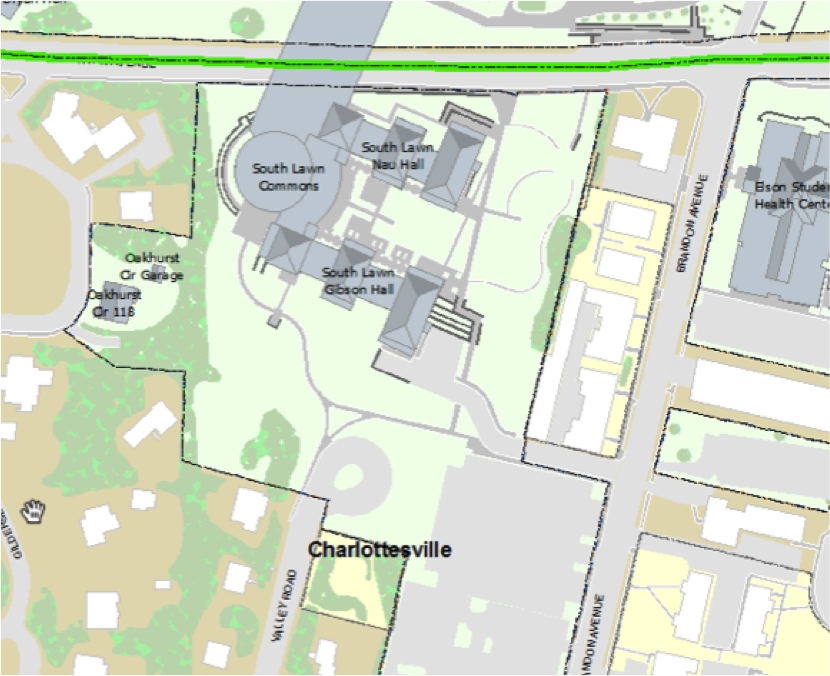

The South Lawn project, the University of Virginia’s largest addition to the Central Grounds area in recent history, highlighted the pivotal function of trees in the ecosystem that is the University of Virginia. Not only do trees provide an aesthetic benefit throughout the Grounds, they also serve the purpose of enhancing energy efficiency for surrounding buildings and creating an environment that fosters learning outside of the classroom. Like the rest of the University, the South Lawn area has a distinct past: during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the area was home to a community of African-Americans and was commonly referred to as the “Canada” neighborhood, according to University of Virginia landscape architect Mary Hughes. Many inhabitants of Canada had ties to the University as employees of the inhabitants of the academical village. One woman in particular, a freed slave by the name of Catherine “Kitty” Foster, purchased and owned a piece of land in Canada in 1833 and constructed a home on the property. Kitty’s home provided a place for University students at the time to store illicit substances such as alcohol and firearms, which were prohibited on Grounds at the time. Long after Kitty’s death, the thoughtfully planned garden around her home and nearby cemetery for the Canada community remained as markers of the land’s history.

From the inception of the planning and design process for the South Lawn project, the project provided a unique opportunity for University of Virginia landscape architects: rather than work around preexisting, historically significant trees, the landscape architects had the opportunity to incorporate new trees and landscape elements into the South Lawn project design because of the asphalt parking lot that existed in its place prior to the construction of Nau and Gibson Halls. Working in conjunction with the architects for the project, Mary Hughes and the rest of the UVA landscape architects developed a plan that honored the history of the site while adhering to native trees in a design that is both efficient and thoughtful. During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, a circle of White Oak trees was planted around what today is known as the Baptist Student Center. These trees lived healthy, long lives, but only two remained at the time that construction began on the South Lawn project. UVA’s arborists took extreme precaution in protecting and preserving the two remaining White Oak trees throughout the construction process and they emerged from the project unscathed. Ironically, lighting struck one of the trees just a week after the construction of the South Lawn was completed and today only one of the centennial White Oaks remains.

Today, the South Lawn Commons area features a constructed park atop the site of the thirty-three graves of the Canada cemetery, representing the lives of Kitty and the rest of the residents of Canada. This park showcases a grove of native Dogwoods around the previous cemetery site- serving as a memorial “frame” for the burials and paying tribute to the lives of those residents. The Dogwoods were chosen by Mary Hughes and the UVA landscape architects specifically to bloom as a simultaneous unit in the spring. However, the trees have struggled to flourish thus far and will be replanted this spring in the hopes that all of the trees will bloom at the same time next year.

In addition to these native Dogwoods, the South Lawn tree planting plans mainly featured a mix of native, mostly deciduous trees, with some evergreens as well. Trees were chosen in particular to create a shaded area on the south side of the South Lawn construction. While the landscape architects had the freedom to implement the trees that they thought would best fit the property in the long run, their decisions were not without constraints. With this project and all University of Virginia planting operations, the landscape architects faced the difficulty of dealing with University Grounds restrictions on that prohibit the planting of any type of tree within ten feet of a water line to prevent later complications with tree roots and water pipes. Furthermore, the south side of the South Lawn area features a large sunken cistern that captures storm water to prevent flooding downstream in the Valley Road community, which had previously been a significant problem. As a result, the cistern prevents any trees from being planted in this area.

The courtyard that exists in the South Lawn area between Nau and Gibson Halls is planted with deciduous Magnolias. This species was chosen intentionally to work with the design of the building- in particular, its significant height. These trees tend to be smaller than other Magnolias, which prevents the courtyard from becoming completely shaded and allows visitors to be able to see the striking architecture of Nau and Gibson Halls. The building wings provide a substantial amount of shade and shelter while the deciduous Magnolias create a pleasant environment in which visitors can study, converse, or simply enjoy the sunshine. The deciduous Magnolias bloom early in the season and represent the first sign of spring in a prominent location for students, faculty, and the like. Deciduous Magnolias sometimes struggle with freezes in the transition from Winter to Spring, but the building wings serve as a form of shelter for the trees and allow them to survive the late freezes that Virginia often experiences.

From inception to completion, the South Lawn project came to fruition through sustained dialogue between the landscape architects and the structural architects of the University. It is both representative of the history of the site and suited to accompany the twenty-first century design of Nau and Gibson Halls.

Post by Natalie Newton, Second-Year, Economics